As New Zealand grapples with a new style of government and approach to the Maori language, Prime Minister Chris Luxon has fallen foul of his advice to the public service.

Mr Luxon appears guilty of a double standard after scolding bureaucrats for taking cash bonuses for understanding the Maori language, te reo, while using taxpayer funds to learn it himself.

Mr Luxon recently confirmed his government would axe payments to te reo-speaking public servants and criticised those who took the bonuses.

"People are completely free to learn for themselves," he said.

"That's what happens out there in the real world, in corporate life, or any other community life across New Zealand.

"I've got a number of MPs, for example, that have made a big effort to learn te reo ... they've driven that learning themselves because they want to do it.

"In the real world outside of Wellington and outside the bubble of MPs, people who want to learn te reo or want to learn any other education actually pay for it themselves."

However, Mr Luxon did not follow his advice.

After repeated requests, the prime minister's office confirmed taxpayers paid for Mr Luxon's classes through a budget offered to the leader of the opposition, saying it was "highly relevant" to his role.

"I think it makes me a better prime minister," he said on Monday.

Opposition Leader Chris Hipkins said te reo was "a national treasure" and learning it should be incentivised.

“Christopher Luxon should be commended for learning Maori, but it’s absolute hypocrisy for his government to then set about cancelling the taxpayer subsidies he used to do so, thus denying others that same opportunity," he said.

Waste watchdog the New Zealand Taxpayers' Union called on Mr Luxon to pay back the tuition costs.

Mr Luxon's right-leaning coalition of the National, ACT and NZ First parties has already strained relations with many in Maoridom, particularly over plans to wind back te reo use as championed by the Labour government.

Public servants have been told to communicate in English while public bodies - such as Waka Kotahi for the New Zealand Transport Agency - must revert to using their English-language name first.

Detractors say the government is bashing a minority and inflaming a culture war while the government argues changes have confused non-te reo speakers.

Te reo use is on the rise in NZ but remains a second language.

Competent speakers have grown from six to eight per cent from 2016 to 2021, including 23 per cent of Maori, up from 17 per cent.

Assimilationist governments banned the language in schools for much of the 20th century, causing trauma for many Maori.

Some government members are hostile to te reo use, with Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters believing Aotearoa, the Maori term for NZ, is illegitimate.

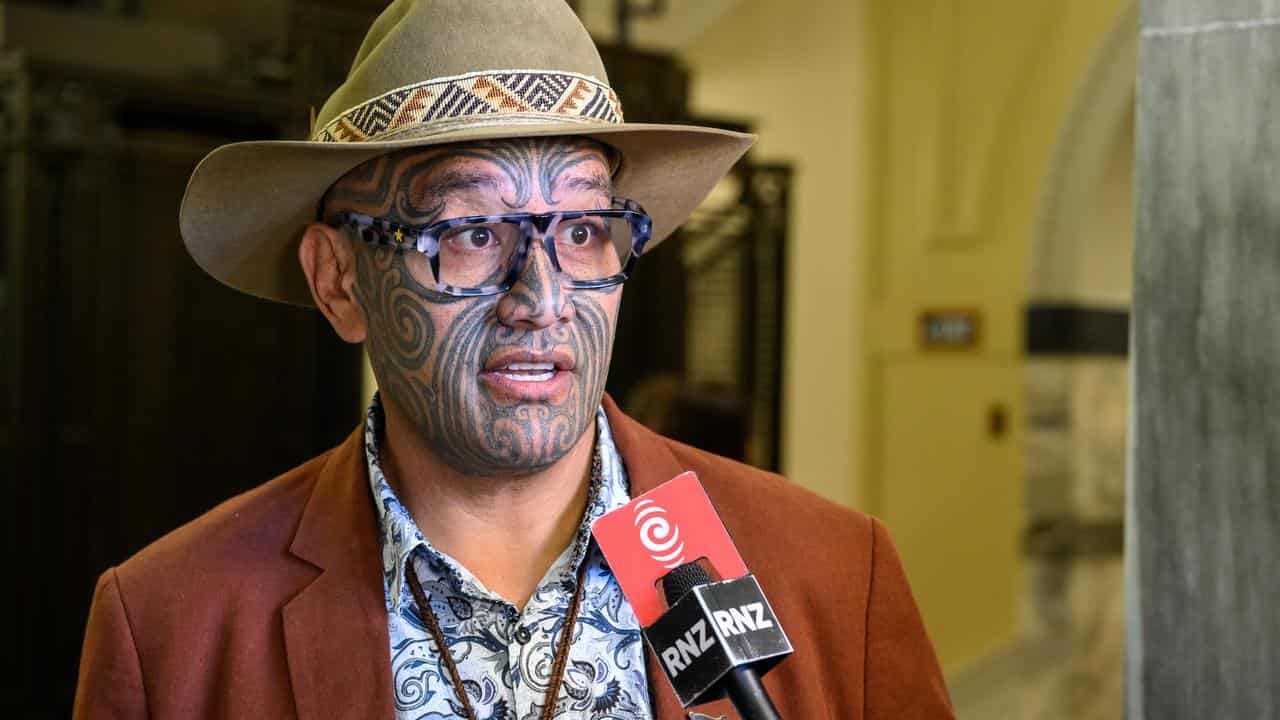

In parliament last week, the 78-year-old declined to answer a question in te reo from Rawiri Waititi, the Maori Party co-leader who has mobilised thousands to protest the new government.

Mr Luxon insisted he supported the language and wanted others to learn too.

"It's a fantastic language," he said.

"I wish I had learned as a younger person ... I'm trying to learn.

"I've found it actually very hard."

Mr Luxon had a chequered record with the Indigenous language in his former role as Air New Zealand's chief executive.

Under his leadership, stewards began using te reo greetings such as "kia ora" for hello and "ma te wa" for see you soon.

In September 2019, the airline sought to trademark "kia ora" - the name of its in-flight magazine.

After consultation with Maori leaders, and a local and international backlash, Air New Zealand abandoned the bid a week later.