When Sharon Deadman was bitten by a tick at her farm on the NSW south coast the allergic reaction was instant.

"I just couldn't stop itching and then my lips started getting tingly," the Manyana resident said.

Within minutes a red rash had spread from her head to her knees, and her face had blown up to be unrecognisable.

At the local hospital Mrs Deadman learnt she was not alone in receiving medical help for a tick bite.

"This year particularly has been bad with a lot of people bitten by ticks. When I was at the hospital they said we've had a lot of people coming in with tick reactions."

Tick bites aren't all recorded as they're not a part of the Department of Health's notifiable disease surveillance system.

Not all ticks carry disease, and plenty of people who are bitten don't need medical help.

While there is no data on how many people are bitten each year, there is health department guidance on severe allergic reactions to bites (tick anaphylaxis) and the mammalian meat allergy, an allergy to red meat that can develop in humans after being bitten.

According to Australia's national science agency CSIRO, the meat allergy is one of the fastest growing food allergies worldwide, with parts of Australia having the highest burden in the world.

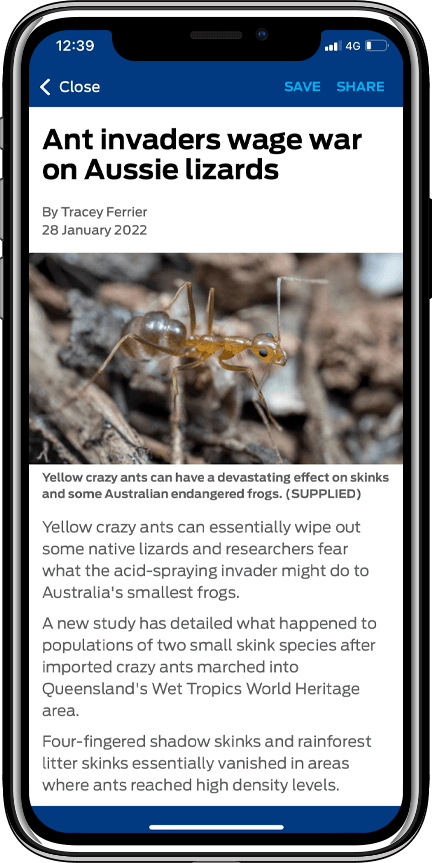

The vast majority of these allergies are associated with the Australian paralysis tick, with much not known about how and why ticks induce the allergy - and almost no work has been carried out on Australian ticks.

"A lot of people I talk to now, have become allergic to red meat," the former nurse told AAP.

"I have eaten red meat and then had some jelly for dessert, I've started getting a reaction."

Now researchers from the University of Melbourne are trying to unlock more information about ticks, including reactions in both humans and cattle.

The researchers have collected around 1500 ticks, from cattle farms across NSW, Queensland and Victoria, in a wide ranging Australian study.

"We have reviewed the literature on ticks and tick-borne diseases in Australia, and we found out that there is a clear knowledge gap in this area," tick expert and lead researcher Abdul Ghafar said.

"We were mainly interested in those properties which are along the coast and which have some bushy areas with wallabies and kangaroos, they are the main transmitters of this tick species," Dr Ghafar said.

Sharon and her husband Allan Deadman are among dozens of producers taking part in the study.

Surrounded by thick bushland, their Murray Grey cattle stud at Manyana, three hours south of Sydney, is considered a tick hotspot.

"We've had a number of journeys to the local vet with tick-affected calves, and it's quite expensive, in the region of $1500 for a hundred-dollar calf," Mr Deadman told AAP.

The cattle breeder who has also lost calves to ticks, does all he can to stop the parasite from biting his animals in the first place.

"We put the tick collars on the calf, that's a given in this area," Mr Deadman said.

"The other thing we do is we light fires around this place too, 'cause I firmly believe ticks don't like smoke," Mr Deadman said.

The cattle breeder has collected three different species for the research team from his cattle stud.

The small brown parasites which can be carried by wildlife, bury into their host's skin. They can be deadly to animals, including calves and dogs.

"The wildlife actually go on to the pastures and they leave the ticks behind, and when the cattle are grazing or any humans pass by, those ticks actually feed on them," Dr Ghafar said.

The study which originally focused on the bush and cattle tick has been expanded to include the paralysis tick too.

"The paralysis tick is important for humans as well as for animals," Dr Ghafar said.

The scientists are also building an artificial feeding system at the University of Melbourne, so they can study the tick colony in the laboratory.

Earlier this year the CSIRO launched its own research program to better understand why tick bites cause the red meat allergy.

Up until then their research had been more broad, analysing ticks to see what type of pathogens they carry, according to research scientist Alex Gofton.

"CSIRO’s research aims to ... provide new insights into how and why tick bites lead to meat allergy," Dr Gofton said.

While there are drugs available to protect cattle and dogs too, there is no vaccine on the market against tick bites for animals or humans and it's something the Melbourne university researchers are also examining.

"That probably would be the ultimate thing is to have a vaccine that's safe for humans to use," Mrs Deadman said.

Researchers are continuing to collect ticks from farmers across Australia, with their study funded for three years.